Application of Style Transfer as an data augmentation technique to improve model’s robustness.

1. Introduction

I attended several Donkey Car meetups during my stay in the US last year and noticed that cars powered by end-to-end neural network (i.e. directly output steering and throttle) weren’t doing as well as the ones that used traditional optimal control methods (such as line following, path planning, etc). No matter how hard people tried, neural network models always lost out to the carefully optimized control algorithms. More frustratingly, most neural network cars couldn’t even complete a single lap during the actual competition when the track was surrounded by audience!

So why didn’t neural network work well and how we, as neural network and deep learning enthusiasts (oh well…), can go about improving neural network cars and even make them viable challengers to the cars powered by optimal control algorithms. In this blogpost, I will discuss some of the major drawbacks of neural network models and outline various techniques we tried to overcome such challenges.

2. Pixmoving Hackathon

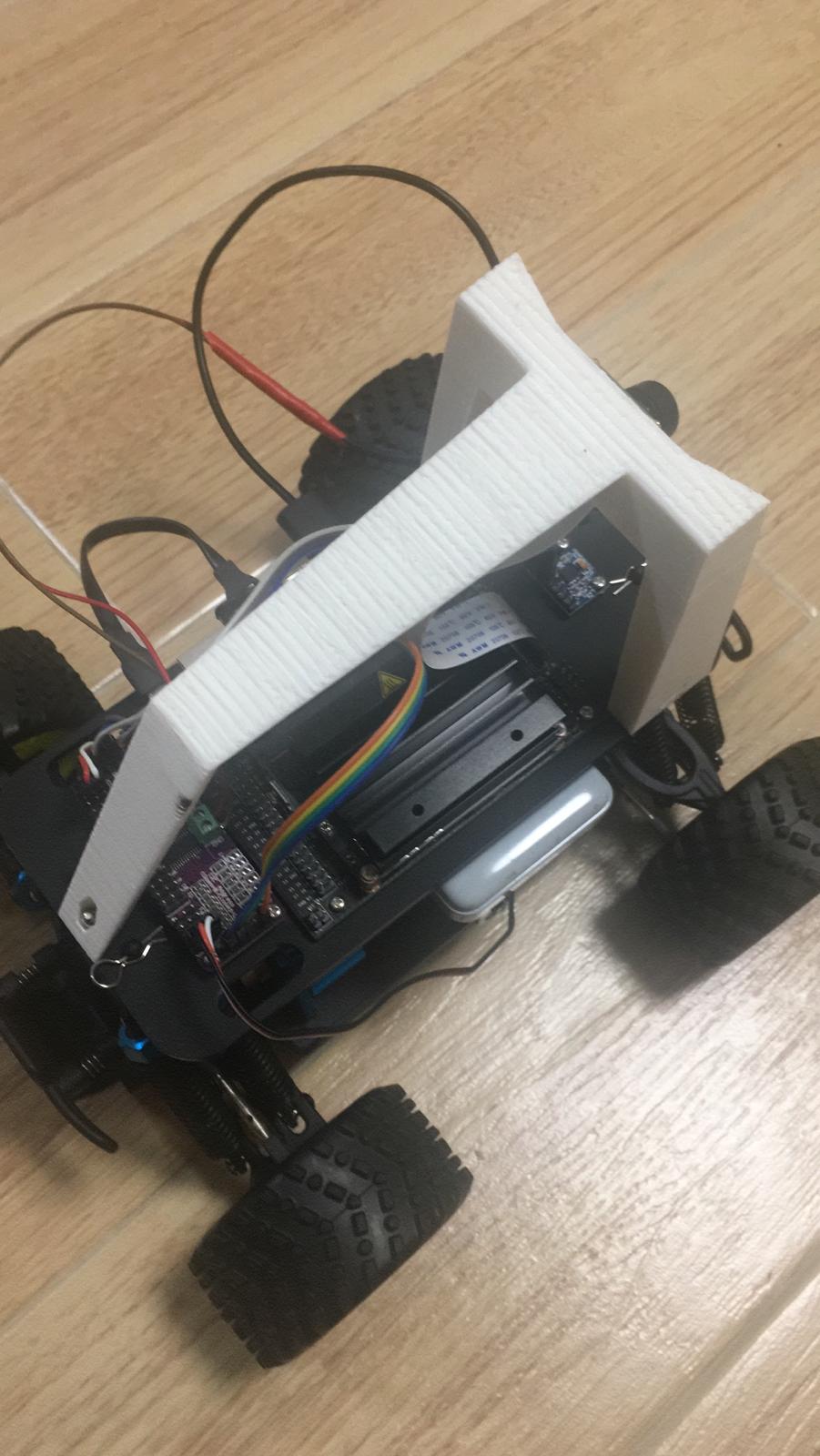

Pixmoving, a self-driving car startup in China, organized a Hackathon event in May 2019 to bring together a group of people from all over the world to gather and try out new ideas on self driving. I had the opportunity to participate in the small-sized cars category together with my friend Fei and Marco. We put together a Donkey Car equipped with the newly released Jetson Nano (replacing Raspberry Pi) to compete in the Hackathon. As compared to Pi, Nano possess a GPU so we are in posession of more computing power to test out ideas on neural network modeling and at the same time achieve better frame rate.

For those of you who want to set up Nano on Donkey Car, feel free to check out this excellent guide written by Fei.

Due to our busy schedule, we were only able to test out the new Jetson Nano car on a downsized track (60% of the full sized track) a few days before the Hackathon (Thanks Hong Kong Society of Autonomous Model Vehicles for providing us the venue). However, it worked pretty well and we had high hope it would work well in the competition too.

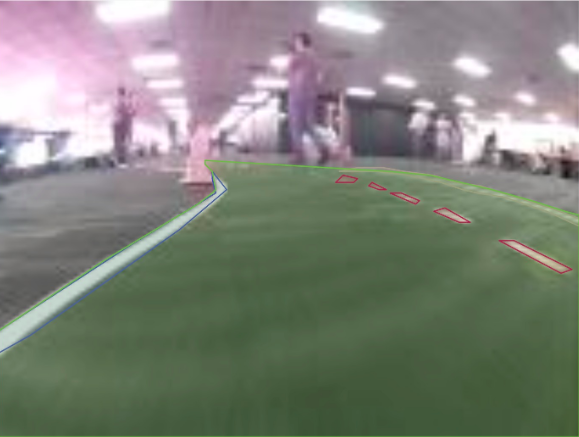

Until we finally arrived at the Hackathon venue and saw the actual track:

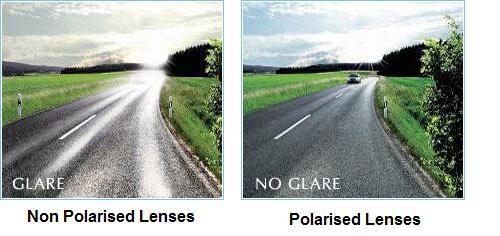

Notice that the track was set up on a glossy surface overlayed with moving shadows and sunlight glares. In addition, the fact that there wasn’t a strong color contrast between the ground surface and the lane lines made the track even more challenging. The undesirable track conditions certainly made things so much tougher; however, we would have the rare opportunity to truly test out the robustness of neural network methods and see how far it could possibly go.

Funny side note: At one point Fei suggested putting polarised lenses on Donkey Car to filter out the sunlight glares. We even tried to secure a pair of sunglasses to experiment the idea. However, we couldn’t find one!

3. Our Initial Attempts to Improve the Model

Our first attempt was to train a baseline model with behavioral cloning. Behavioral cloning works by first collecting a set of training data through manual driving, and then train a convolutional neural network (CNN) to learn a mapping between car images (taken by the front camera) and the recorded steering angle and throttle values through supervised learning.

As expected, out of the box behavioral cloning did not work so well. It failed miserably whenever the car encountered shadows and sunlight reflections, but they are literally all over the track. Sometimes it failed simply because people were moving in the background, a strong evidence that the neural network model actually overfitted to the background instead of the track.

We subsequently tried various things on the modelling side:

3.1 Stacked Frame

Instead of using a single RGB frame as input to the neural network, we stacked together 4 grayscale frames from consecutive timesteps as input to the model. This was for the model to pick up important temporal information by learning subtle changes from successive frames.

3.2 Recurrent Neural Network (LSTM)

We also trained a LSTM model with 7 timesteps to capture more information from the temporal dimension. For each time step, a 3 layer CNN was used to extract feature from the raw RGB frame, which was then used as input to the LSTM model.

3.3 Reinforcement Learning

Prior to the competition, I trained the car to drive successfully on a simulator with Reinforcement Learning. If you are interested in how I did it, please refer to my previous post. The reinforcement learning algorithm I used to train the model was Double Deep Q Network (DDQN).

While my initial idea was to try out zero-shot simulation to reality (i.e. train the model entirely on the virtual track and deploy it right away on the real track), however, due to the huge discrepancy between the virtual and real track, I resorted to simply using the DDQN model to initialize the neural network weights and then use the data we collected on the real track to do supervised learning.

My hope was to improve the data efficiency of behavioral cloning so we did not have to collect that much data to get the model working. In addition, having an RL pretrained model might also have the added benefit of improving the overall robustness of the resulting model. It is known that data collected by human demonstration and the model trained from the data thereof isn’t very robust, since the data collected by human is heavily biased towards some states over the others.

Much to our dismay, none of the above methods contributed significantly to the car performance. Our car still struggled to make a full lap. We had to come up with other ways to make the car more robust to varying conditions on the track.

4. Robustness Issues with Neural Network Behavioral Cloning

As mentioned, Behavioral Cloning works by using a CNN to learn a mapping from RGB images to steering and throttle (i.e. end-to-end training). Ideally, the CNN model would learn that the lane lines are what matter, and that the objects in the background and shadows/reflections on the track area are useless information that should be dumped out.

However, due to the way CNN (or neural network in general) works, the model have a tendency to overfit to the most distinguished features in the image, which in our case were the objects in the background and light reflections on the track.

The above video is the saliency heatmap of our baseline CNN model trained by behavioral cloning. The heatmap was generated based on the code provided by this repo. The idea is to find parts of the image that correspond to locations where the feature maps of CNN layers have the greatest activations, in other words, the heatmap shows where the model is “looking at” when making its decisions.

To fully test out the generalization ability of the model, the dataset we used to train the model and generate the heatmap are collected from 2 different days under varying lighting conditions and surface reflection intensities. Notice the model’s focus was almost entirely on the background objects and sunlight reflections, anything but not the track lanes. As a result, it wouldn’t be a surprise that the model failed miserably when any of the background objects were changed/moved or when there were sunlight reflections. The model trained from raw images was very fragile!

5. Computer Vision Techniques to Overcome Variation in Track Conditions

Our next attempt was to use computer vision techniques to cut out the background objects and eliminate the sunlight glares from the track. We first tried to see if we can use some kind of edge detection (e.g. Canny Edge Detector) + Hough Line Transform to segment out the lane lines from the images. In my previous blog post, I’ve briefly covered using such method to segment out the lane lines in the simulator. However, upon some quick experimentations, it became clear to me that this method wouldn’t work on the real track. For example, for the image below with a strong marking of sunlight glare:

The edge detector failed even to capture the lane line!

We subsequently tried to use color thresholding to extract the lane lines by first projecting the RGB space into HSV space and find a proper threshold to separate the lane lines from the image. It turned out that instead of extracting the lane line from the image, it’s easier to devise a threshold to extract the sunlight glare, since its color is more distinguishable from the background.

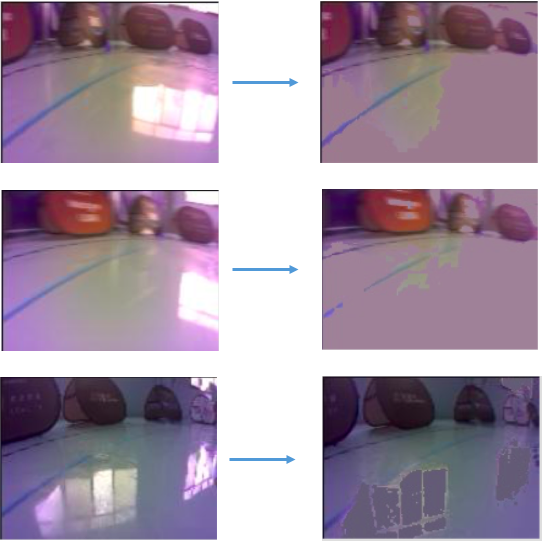

We used the above threshold technique to mask out the sunlight glare from the image and fill in the void with the mean pixel from the images. The result looks like this:

Our method successfully filtered out most of the sunlight glares. Notice that there might be false positives (i.e. the method mistakenly filtered out part of the track that wasn’t from sunlight glare), but their effect should be insignificant and they can even be treated as a form of regularization to avoid overfitting to the background!

And there you go, the car was able to successfully maneuver through the random sunlight glare patterns on the track!

In contrast, cars trained with raw images without going through such preprocessing step would just ran into loops whenever they encountered strong sunlight glares.

However, the resulting model even after filtering out the sunlight was still not very robust. Though it was able to complete a full lap and somewhat able to overcome the randomness sunlight glare patterns, it failed to do so consistently. For example, in the event where there are people moving/walking around the track, background objects being changed/moved, or the sunlight intensity dropped due to evening approaching. It became clear to us we have to try alternative methods to further improve the robustness of the car.

6. Style Transfer to Achieve Robustness

This is when Marco recalled a paper he read a few years ago that used a technique called style transfer to augment the training dataset so that the model is more sensitive to important features such as lane lines and ignore the unimportant patterns such as background objects and track surface.

We applied 3 different and distinctive styles (i.e. the Scream, Starry Night, Candy Filter) to the set of training images and below is the visualization of dataset after style transfer:

(Top Left: Original, Top Right: Candy, Bottom Left: The Scream, Bottom Right: Starry Night)

After some eyeball inspection we found out that the lane lines actually got strengthened during style transfer, while the background objects and track surface patterns were somewhat smoothed out! Hence, we could use this augmented dataset to train the model to focus more on the lane lines and becomes less sensitive to background objects.

We trained a model using the style transfer dataset together with the original dataset and its performance and robustness enhanced significantly as compared to our previous baseline model! Models that were previously failed due to change in track reflection intensities and moved background objects were suddenly working!

To examine if our model was really focusing on the track lanes, we generated the same saliency heatmap for the style transfer model on the same dataset we used to test our baseline model above:

We noticed that the style transfer model, while still overfit to the background occasionally, has a much stronger focus on the lane lines. In contrast, our baseline model almost never look at the lane lines at all! In our opinion, style transfer can be effectively used as a data augmentation technique to improve the generalizability and robustness of the model, especially when the dataset is small or we want the model generalize to a new track.

7. Failed attempt on Segmentation

Prior to the Hackathon, we were well aware of the fragileness of using end-to-end neural network for driving. In an attempt to filter out the background noise, we tried to train a semantic segmentation model to extract the lane lines from the images. We spent hours labelling the lane lines and ended up putting together a dataset of around 130 images with 4 classes: left lane, right lane, middle lane, track area.

One of the main reasons we decided to replace Raspberry Pi with Jetson Nano was so that we would have enough computing power to incorporate the segmentation model to the inference pipeline. Our plan was to first pass the raw RGB frame to the segmentation model and obtain a mask for the lane lines, then use the mask as input to the behavioral cloning neural network.

Here is the list of our approaches in chronological order before we decided to stop as we did not have enough time:

- Wrote unit test for data loader.

- Implemented data loader which passed the unit tests.

- Visualized data loaded from data loader in notebook, make sure once again the data is looking fine.

- Modified U-Net Keras architecture from existing GitHub repos.

- Wrote unit test on U-Net model for checking gradients are passed through in each layer.

- Implemented our own DICE loss.

- Overfit one batch of data. Failed to reach train loss = 0. (Plateaued at high number)

- Only load the track mask instead of loading all 4 masks, still cannot reach 0 train loss.

- Found out that we did not map image range from [0, 255] to [0, 1]. Fixed that

- Overfitted one batch of data to train loss 0.

- Train with all data and track mask label only. Convergence were very slow.

- Looked at the predictions image, all the pixels are 0.

- Added L1 loss to regularise the training because we want to encourage sparsity. Training became much faster but both train and valid loss plateaued.

- Looked at the predictions image again, all the pixels are 0 still.

We suspected we simpy had too few training data to get the segmentation model to work.

8. Hackathon Results

The winning criteria for the competition was fastest single lap time. Due to the unexpected difficulty of the track (there was also a rain storm in the midst of the competition), the officials decided to give each of the 11 teams unlimited number of trials! Basically, there was a timer stationed by the track and whenever we were ready we just signified the timer to time the lap for us. I know the format was a bit weird and it sort of encouraged teams to overfit massively to the background, since we had unlimited number of trials and only needed 1 fast lap to win.

This was exactly what happened and the best lap times were recorded during the moment when the background and lighting were relatively stable (i.e. when the sun was behind the clouds and the surroundings of the track was cleared). Our best lap time was 12.67s and ended up at the 4th place, trailing the 3rd place team by a mere 0.02s! Well, part of the reason was that we had to leave the competition 1 day early (we could not afford to take an extra day off…..) so we literally gave up half a day worth of opportunities to further boost our best single lap time!

9. Lessons Learned:

9.1 Simple model + good dataset can go a long way

From our experience in the hackathon, all the significant improvements came from improving the quality of the training dataset instead of model innovation. All our attempts on improving the model, including using stacked frame, LSTM, altering neural network architecture, and fine-tuning on RL models did not make a significant contribution to the performance. On the other hand, innovation on improving the quality of the dataset, such as CV preprocessing, style transfer to augment the dataset led to significant performance boost.

In fact, the winning team, with the best lap time of 9.75s, simply trained a baseline model on a carefully collected dataset. He showed us how he placed extra attention to collect good data (i.e. send clear, strong, and consistent steering signal) at the more difficult parts of the track.

This kind of echo with OpenAI and Tesla’s philosophy of approaching AI problems not by innovating on the model but to scale up computing infrastructure to learn from high quality dataset.

9.2 End-to-end neural network model is still lagging behind optimal control methods

With 2 days of unlimited trials, the best lap time of 9.75s is still significantly lags behind the best optimal control car (@a1k0n) with the best lap time of ~8s. Even with data augmentation and regularization techniques I don’t think end-to-end neural network models would ever pose a serious challenge to optimal control cars.

Neural network excels in areas where traditional optimal control methods fail to capture the underlying dynamics, such as training a human-like dexterous hand to manipulate physical objects, performing controlled drifting!. We should understand its limitation and only use it in appropriate settings accordingly but not blindly throw it to all problems especially on problems where optimal control already have the solution.

10. Acknowledgement

I would love to thank Pixmoving for organizing such a great event! The venue was amazing and we had the opportunity to try out many ideas which otherwise would be difficult to try out. I would like to thank Robin for helping me out with Unity. Last but not least, my teammates Fei and Marco for participating in the Hackathon with me and came up with so many brilliant ideas!

If you have any questions or thoughts feel free to leave a comment below.

You can also follow me on Twitter at @flyyufelix.